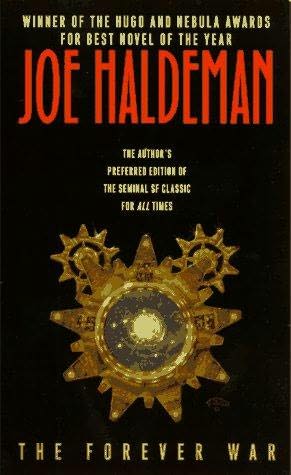

I'm cheating a bit with this entry, because Joe Haldeman is far from discount bin material(The Forever War is widely regarded as one of the 20 best sci-fi books of all time, which is an amorphous but still impressive honor), but considering how often sci-fi is marginalized in popular culture, I'm willing to allow it. Plus I made up the rules, and if you don't like it, tough.

I'm cheating a bit with this entry, because Joe Haldeman is far from discount bin material(The Forever War is widely regarded as one of the 20 best sci-fi books of all time, which is an amorphous but still impressive honor), but considering how often sci-fi is marginalized in popular culture, I'm willing to allow it. Plus I made up the rules, and if you don't like it, tough.I am not, typically, a sci-fi aficionado. I'm changing that, slowly, with this 'Discount Bin' feature, but it's still a genre that I'm largely ignorant of, and as such I have a fairly basic way of categorizing science fiction novels into two categories; soft sci-fi and hard sci-fi. Hard sci-fi is where the science is front and center, and dense, and often meticulously researched. Soft sci-fi is where the science exists merely as a kind of rack to hang the story on, and isn't explained more than is necessary to propel the story. Hard sci-fi is often full of big mind blowing ideas, but often, by design, is not very emotionally engaging. On the other hand, soft sci-fi, which I have to admit I usually enjoy more, is more geared towards exploring emotional and philosophical questions and uses the science as a starting point. The works of Samuel Delaney would edge towards hard sci-fi, while the works of Kurt Vonnegut would be clearly soft sci-fi.

I shared this viewpoint with my friend Eric, and it turns out he had a complimentary way of categorizing science fiction. He viewed sci-fi as either space opera or deconstructive. Space Opera was basically our myths transplanted to space, a way of reaffirming the truths we hold dear. Deconstructive sci-fi was the opposite, and used the medium to explore, subvert or argue against the ideals we as a society hold on to. Star Wars would be space opera, while Star Trek would be deconstructive(actually, it would bounce all over the place, since they tried to do so many different things with that show). If you were to take those and form a quadrant graph, with each corner of a square devoted to one category, The Forever War would form a pretty symmetrical shape smack dab in the middle.

The Forever War starts in the mid nineties where humans are much more technologically advanced, having discovered near-light speed travel(aided by wormholes which advanced the study of physics dramatically). When one of their research ships comes back horribly damaged, and all of it's crew dead, the military minds become suspicious. When first contact is made with an alien race(dubbed Tauran), humanity shoots first and asks questions later. So begins the Forever War, where the military drafts not dropouts, but the smartest and strongest college students(wanting physicists who would understand the technology needed), and then sends them out into deep space. If they survive, they will return to an Earth several generations on, where everyone they know is dead and everything has changed.

Given the option to resign after his first two year tour, William Mandella returns to an Earth several decades on. His father is dead, but his mother is alive, and Earth is suffering from the effects of a war that steals the strongest and brightest of it's children. He and Marygay, whom he developed a relationship while in space, find themselves unable to fit in to this violent, soul-deadening society, despite being immensely wealthy(military pay plus several decades of interest in their Earth bank accounts), and re-enlist as instructors. The army has other needs, and sends Mandella and Marygay back into battle. And so it goes. The two are sent back into the war, together for awhile until separate assignments make it impossible that they would ever see each other again(relativity being what it is, they will most likely die hundreds of years apart). Occasionally Mandella returns to Earth, or at least to humanity, to gear up with the latest technology and head back to the aptly named Forever War.

There are so many ideas in this book that I don't really know where to start. The science is at the forefront, and each idea is theoretically possible with what we know(or knew, in 1974) of physics. And yet, unlike some novels I've read, the technical details never go too far into mind-numbing statistics. Scratch that, it goes VERY far into the statistics, theories and practical uses of the technology, but it was like a really amazing PBS documentary that makes you want to go out and research the scientific theories at work. Much of this science is applied in weapons, of course, and there are some really fascinating things there, but a lot of it is also given over to relativity and the disorienting affects it has. It's one thing to leave for two years and come back to find Earth is 20+ years on, it's another to never know what type of enemy you're going to run into, whether they will be more or less technologically advanced than you. On first contacts, the Taurans prove to be horrible fighters, completely ignorant of warfare. They have some devastating weapons in space, but on ground they seem to have no concept of hand to hand combat. This changes as things go on, but it's never steady. They never know if, due to the physics of time travel, they will run into a group of Taurans that left port earlier, the same time as, or decades later than the humans did.

I think what makes The Forever War so distinguished among other Hard Sci-Fi books I've read is that he's applied the same conjecture to the social, emotional and philosophical ramifications of such an immense and expensive war. Each time Mandella returns to Earth, we are told of all of the changes on Earth, but also given explanations for how things got that way. For an arm-chair doomsayer like myself, all of it seemed completely plausible, and a bit more subtle than the average 'descent into savagery and fascism' than most sci-fi has. At several points Earth is even better off than when Mandella was drafted, since these things tend to go in cycles; things get better, things get worse.

By the end of the novel, Mandella has lived through over 1,000 years of human history, although of course it's been less than a decade for him. Towards the end he keeps getting sent out on missions because, as the oldest soldier, and one of only a handful to survive more than two encounters, he's become a folk hero, something for the propaganda machines on Earth to celebrate. The ending pulls out some sudden emotion, which seems slightly out of place against the fairly grim and emotionless events recounted prior, but it still gave me chills, and was immensely satisfying. I won't spoil it here, because it's a book that has surprises on almost every page, and really should be enjoyed blind(I've been careful to avoid some of the bigger shocks). I will, by necessity, be spoiling the ending when I review the sequel, but I'll give you all a few days head start.

I know I recommend stuff all the time, but right now I'm going to say that anyone reading this on a regular basis needs to go buy this book as soon as possible. I'm gushing, I know, but it really was a great book and surprised the hell out of me.

No comments:

Post a Comment