Desperate provides a great counterpoint to Hollow Triumph, a film I wrote about not too long ago for this project. Both films feature a plethora of illogical character decisions and ridiculous scenarios, but Desperate offers an example of how to keep that from becoming an insurmountable problem. Both Desperate and Hollow Triumph center around characters who make needlessly complicated and ill advised decisions throughout, but with several dramatic difference. First, the issue of pacing. Hollow Triumph is leisurely at times, and Desperate rushes along at a brisk 73 minutes(sometimes, I must admit, this is to the film's detriment; one segment that seems to span several days is revealed to have spanned 6 months). The second major difference is that of motivation.

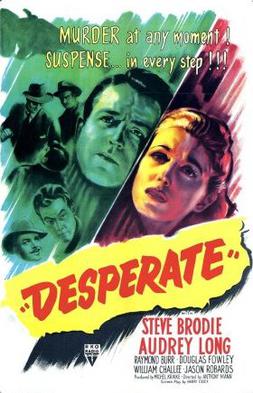

Desperate provides a great counterpoint to Hollow Triumph, a film I wrote about not too long ago for this project. Both films feature a plethora of illogical character decisions and ridiculous scenarios, but Desperate offers an example of how to keep that from becoming an insurmountable problem. Both Desperate and Hollow Triumph center around characters who make needlessly complicated and ill advised decisions throughout, but with several dramatic difference. First, the issue of pacing. Hollow Triumph is leisurely at times, and Desperate rushes along at a brisk 73 minutes(sometimes, I must admit, this is to the film's detriment; one segment that seems to span several days is revealed to have spanned 6 months). The second major difference is that of motivation.John Muller in Hollow Triumph made stupid decisions under the guise of intelligence; we the audience were expected to believe he was an intelligent man taken down by karmic retribution, when really he led himself to that end one idiotic step at a time. He was an egotistical, selfish man who made his own bed. Steve Randall(Steve Brodie) in Desperate is an innocent, sucked into an awful situation without the luxury of planning or experience. He makes the wrong decision again and again, and yet he does it all out of a desire to protect his wife. A simple change in motivation ends up making all the difference, as Randall is immediately more sympathetic and identifiable.

The film begins with Steve coming home to celebrate his 4 month anniversary with his wife, who is making a cake for the occasion. A corny situation that sets this couple firmly in the idealistic, sunny world you often find in post-war romantic melodramas. Their celebration is postponed when Steve gets a call offering him a job hauling merchandise for $50. That's not the stupid decision, actually; Steve is a freelance trucker/delivery driver, and does jobs like this all the time. The first stupid decision belongs to gang leader Walt Radak, who knows Steve from their childhood, and somehow believes it would be a good idea to hire an outside agent to be his getaway driver from a big heist and not tell him about it.

Steve's first stupid decision, pretty much the one he keeps making throughout the movie, is to not go to the police when he has the chance. After escaping the gang's clutches for a second time, after a botched first attempt leaves him bruised and bloodied, Steve should have gone directly to the cops. However, Walt had threatened to kill Steve's wife Anne(Audrey Long) if he didn't take the fall for the murder of a cop killed in the heist, so his focus was entirely on Anne's safety. Seems to me that the cops would have been able to provide more protection than Steve's 'lets run to the country' plan, but he was caught off guard and scared. I'm willing to cut him some slack for not thinking entirely rationally at this point.

Much less forgivable are some of Steve's other stupid decisions while on the road. After being swindled out of $90 by a used car salesman, Steve steals the car he has, to his credit, actually paid for. When a cop picks him up and begins to take him back Steve takes advantage of a small wreck to steal the cop car and go on the run. It's easy to justify these thefts, and Steve isn't anywhere close to being a bad guy, but it should be clear to any audience member that he's behaving foolishly. My heart sank a bit each time he stole a car, as it lowered his stature in my eyes a little bit.

Steve and Ann eventually make their way to the farm of Anne's parents, where they are welcomed with open arm into a rustic life of warmth, happiness, and post-war wholesomeness that rivals even the domestic bliss they felt at the beginning of the film. Steve goes to the police and comes clean about his involvement in the heist, and is told he's completely in the clear on that score. But that turns out to not be the case when Walt Radak shows up in town, no longer looking to force Steve into taking the fall, but looking for revenge for his brother being sent to the chair. Time for another move.

You see what I mean about Steve making the same stupid decision over and over again? He even tries to run again later in the film, hoping to make it all the way to California. If that hadn't been far enough I'm sure he would have been on his way to Mexico in an instant.

I've been using the idea of noir films existing as a sort of purgatory quite a bit, but a new metaphor came to mind during this film. In Desperate the film noir elements felt more like the threat in a Japanese horror film, a curse that could be passed on to an innocent person on contact. A curse that you could never outsmart or outrun, that would find you no matter where you ran, that could only be stopped by means of a violent bloodletting. Every time Steve and Anne made it to a new place, the film would become bright and sunny, but eventually the shadows would creep in, and the gangsters would show up, and Steve and Anne would be forced to try and run yet again.

Steve and Anne begin the film in a state of domestic bliss, living in a picture perfect ideal of marriage. The film is brightly lit, comedic even, and there's one instantaneous edit that changes everything. Steve gets the note telling him to call a potential client, and heads to the hallway phone to make the call. The phone is in a clean, bright hallway, and the film cuts on Steve's hopeful face as the phone rings to a shot of the phone on the other end of the line. It hang on a dirty grey wall in a room filled with inky black shadows, and from that transmission from Noir Country Steve and Anne's lives are changed forever. When we cut back, the scene looks the same, but something has changed. There are notes of concern, and the threat of menace hangs over everything.

This is a repeating motif in the film; Steve keeps escaping to places that seem perfect, but the shadows always creep in. They go to work on Steve as well, as he turns to car theft and compromises his morals to keep his wife safe. Noir in Desperate is like a physical disease, a body horror where the body is the movie itself.

OK, maybe that's stretching things a bit, but my point is clear. Noir leaves a stain that isn't so easy to get rid of.

_02.jpg)

_01.jpg/220px-Poster_-_On_Dangerous_Ground_(1952)_01.jpg)